Notes on Epistemology and Bounded Rationality

1. Expectationally-Driven Market Volatility, an Experimental Study

R. Marimon, S.E. Spears, S. Sunder

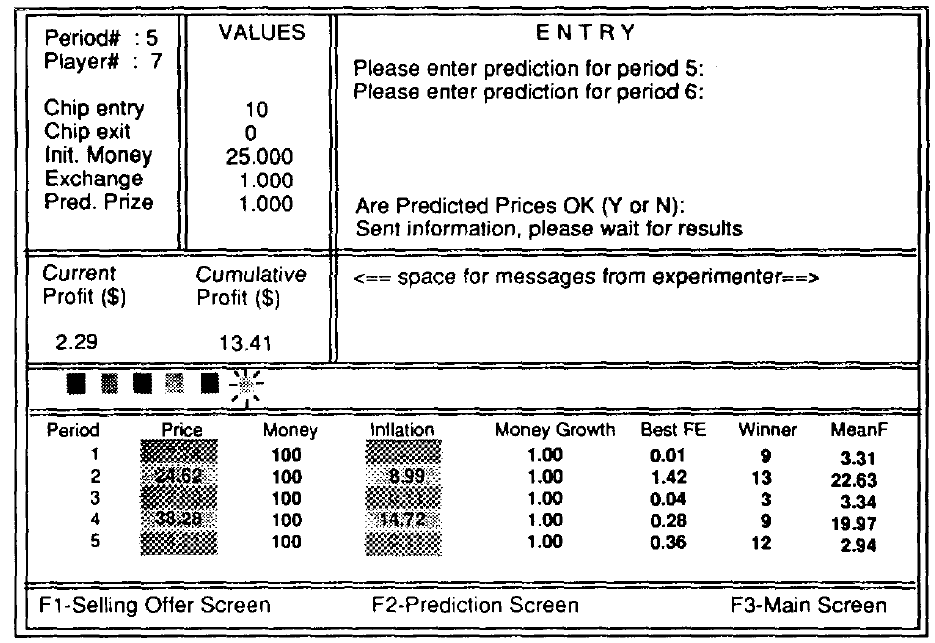

Marimon, Spear and Sunder suspect that random extrinsic shocks can lead individuals to form beliefs about future behaviour in a market. For example, one might conclude from historical data that sunspots influence weather on earth and therefore affect changes in commodity prices \ref{sunspots}

The self-fulfilling prophecy is, in the beginning, a false definition of the situation evoking a new behaviour which makes the original false conception come "true". This specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error. For the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning.

Robert K. Merton, Social Theory and Social Structure

How can agents obtain false definitions, and how is this different from actual knowledge about the system they are observing?

The Sophists' definiton of Knowledge

An agent knows proposition $P$ is true $\iff$

- (i) is True

- (ii) The individual believes $P$ is true

- (iii) This belief is justified

In the Theaetetus Plato exhibits the dissatisfaction that Socrates and Theaetetus have with the Sophists' definition. The history of epistemology is full of criticisms and refutations of this definition of the Justified True Belief but the most well known is the 1963 paper by E. Gettier "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?"

Counterexample

From Gettier's paper, take for example Case 1

CASE I

Suppose that Smith and Jones have applied for a certain job. And suppose that Smith has strong evidence for the fol1owing conjunctive proposition:

(a) Jones is the man who will get the job, and Jones has ten coins in his pocket.

Smith's evidence for (a) might be that the president of the company assured him that Jones would in the end be selected, and that he, Smith, had counted the coins in Jones's pocket ten minutes ago. Proposition (a) entails:

(b) The man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket.

Let us suppose that Smith sees the entailment from (a) to (b), and accepts (b) on the grounds of (a), for which he has strong evidence. In this case, Smith is clearly justified in believing that (b) is true.

But imagine, further, that unknown to Smith, he himself, not Jones, will get the job. And, also, unknown to Smith, he himself has ten coins in his pocket. Proposition (b) is then true, though proposition (a), from which Smith inferred (b), is false. In our example, then, all of the following are true: (i) (b) is true, (ii) Smith believes that (b) is true, and (iii) Smith is justified in believing that (b) is true. But it is equally clear that Smith does not KNOW that (b) is true; for (b) is true in virtue of the number of coins in Smith's pocket, while Smith does not know how many coins are in Smith's pocket, and bases his belief in (b) on a count of the coins in Jones's pocket, whom he falsely believes to be the man who will get the job.

Overlapping Generations

For experiment 1 through 4 in the paper we propose the following:

- The subject sees that the colour of the light is in phase with the price in the market

- The next colour of the light alternates

The test subject has strong historical evidence to believe that the colour of the light changing from (red, yellow) is associated with the market going (up, down).

In "A Causal Theory of Knowing" A. Goldman proposes a change to the definition of knowledge to prevent the Gettier problem.

- $P$ is True

- The individual believes $P$ is true

- This individual has arrived at this belief though a some reliable process

Recall Tversky and Kahneman: _Representativeness is the degree to which [an event] is similar in essential characteristics to its parent population reflects the salient features of the process by which it is generated

The researchers take great care to make the elements of the external signal (the light) be representative for the market price in the user interface presented to the test subjects. The event (coloured lights) are general enough to describe an extrinsic variable as opposed to a numerical indicator. This allows test subjects to come up with various beliefs about its purpose and the relation to the market.

Generality objection:

A process (by Goldmans definition) always generates either justified or unjustified beliefs.

Counter Example A tennis umpire determines whether a ball was in or out of bounds. Some cases are obvious, some are hard. * Using the same process, his belief would be equally justified in both cases

Gilbert Harman's defeasibility requirement states:

One knows only, if \textbf{there is no such evidence such that if} one knew about the evidence, one would not be justified in believing one's conclusions. --- Gilbert Harman, (Thought)

Example for Case 1: Smith would not hold his beliefs if he knew Jones would not get the job.

Accepting the defeasibility requirement for the experiment, we must also accept that subjects do have expectations about the light signal as long as they don't find the following evidence:

- test subjects are told in the manual the light always alternates

- In experiment 5, or having knowledge about previous experiments, subjects quickly learn that alternating light does not always relate to price movements

Also: experiments do not continue for a long time after the shocks/events stop.

As soon as agents lose their beliefs in the light signal, they lose the most important \emph{Keynesian Uncertainty} about the game. Instead, agents will create expectations about the distribution of random exogeneous shocks, independent of the signals.

Ideas

The main think I would do differently is to maintain uncertainty about the signal

- by adding noise,

- removing the text from the manual, or

- testing with multiple indicators at the same time, some of which completely random

Summary

- The results show that there is no creation of persistent volatility without exogenous shocks

- [Statement] This can be done reliably (clear signal)

- Subjects must be conditioned to expect cycles

- [Statement] I think this leads to rational expectations about the occurrence of exogeneous shocks as opposed to beliefs about the signal(s)

Paper retrieved from UBA.

Abstract

We study the existence and robustness of expectationally-driven price volatility in experimental overlapping generation economies. In the theoretical model under study there exist "pure sunspot" equilibria which can be "learned" if agents use some adaptive learning rules. Our data show the existence of expectationally-driven cycles, but only after subjects have been exposed to a sequence of real shocks and "learned" a real cycle. In this sense, we show evidence of path-dependent price volatility.

Published In: Journal of Economic Theory (Vol. 61, No. 1, October 1993, pp. 74-103)